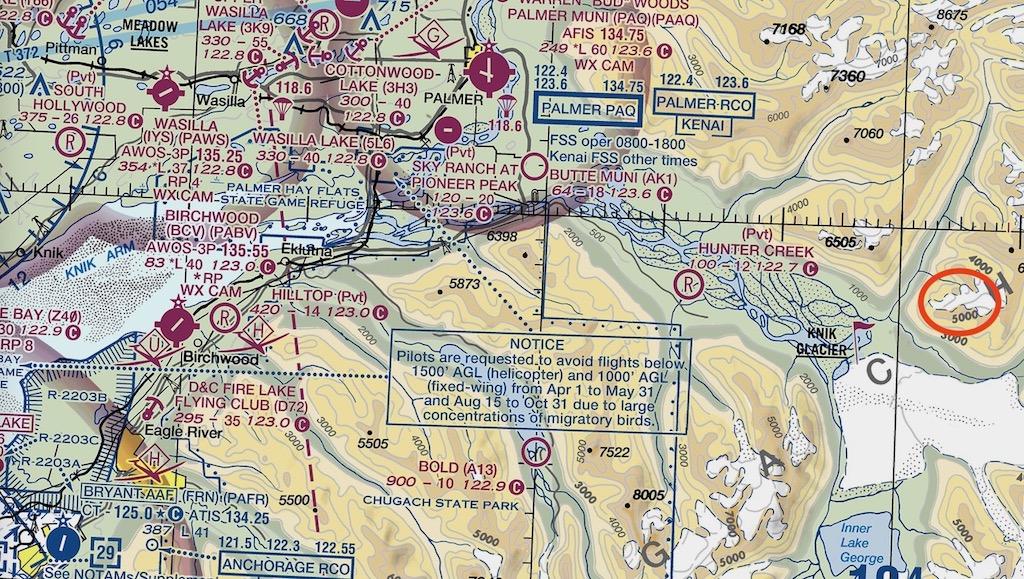

Anchorage, Alaska, sectional chart showing location of the helicopter accident.

The main wreckage of the AS-350B3 ski-tour helicopter came to a stop on its right side about 500 ft. below the top of the ridgeline. Additional debris extended down to about 900 ft. below the ridge. The emergency locator transmitter (ELT) was still attached to the airframe, but its external antenna was missing.

The NTSB’s airworthiness group examined the main wreckage in the month following the March 2021 accident, but other wreckage wasn’t recovered for over a year. The investigators did not find any malfunctions or failures that might have caused the accident.

The first person the NTSB interviewed was the surviving passenger. He had suffered severe frostbite, rib fractures and contusions, and hypothermia so severe that his body temperature was only 28 degrees C when he was rescued. The interview was 11 days after the accident and was done using FaceTime. He said the pilot first attempted to land but then “went up to try to get into the right position.” The snow was “really light” and as the pilot tried again to land, the helicopter was “engulfed in a fog, which made it appear like a white room.”

The surviving passenger confirmed that it was the passenger sitting to his right who had cried out “no, no, no, don’t do it!” He had been skiing with both of the other passengers for 10 years or more. He said the pilot was having trouble staying level on the earlier drop-offs, and the helicopter wasn’t level when they touched down the first time. He also said the pilot was new.

When safety investigators later interviewed operator Soloy Helicopter’s director of operations and other company officials, one of their areas of focus was on the pilot’s experience and training.

The pilot, 33, held a commercial pilot certificate with rotorcraft helicopter and instrument helicopter ratings. His FAA first-class airman medical certificate was dated Feb. 10, 2021, and there were no limitations. He had logged 3,286 flight hr., of which 1,505 were in the make and model of the accident aircraft. He had flown 178 hr. in Alaska, 105 hr. of heli-ski flying, and a total of 59 hr. of simulated instrument time. Soloy’s safety manager called him a “journeyman” pilot, not a high-time pilot compared to other pilots at Soloy.

Before coming to Soloy, the accident pilot had flown Grand Canyon and Monument Valley tours with Sundance Helicopters and glacier tours in Juneau with Northstar Helicopters. He first started working part time for Soloy in 2019, flying oil drillers. In 2021, he was flying heli-ski operations in a contract with Chugach Powder Guides before he was asked to fly the Tordrillo Mountain Lodge contract.

When the accident pilot first took his instrument helicopter check in 2013, he was disapproved for “performance maneuvers.” Later, he also was disapproved on his first attempt to complete his flight instructor instrument helicopter rating. The areas he had to repeat were “flight by reference to instruments” and “instrument approach procedures.”

The visual condition the surviving passenger described was a “white-out,” and it was probably caused by the helicopter’s rotor wash while the aircraft hovered over the ridgeline. Given the pilot’s relatively low experience in Alaska and possible poor instrument proficiency, he may have been unprepared to cope with the situation.

Safety investigators examined the pilot’s training at Soloy. The company’s Controlled flight into terrain (CFIT) training for the pilot could not be verified, and he had not been checked for proficiency in recovery from inadvertent instrument conditions, ATC communication, and instrument approach flying.

Other Factors

The accident helicopter’s instrument panel was recovered virtually intact. It had a full set of flight instruments, including attitude and directional indicators, altimeter and vertical speed, airspeed and even a radar altimeter. The pilot should have been able to transition to instruments long enough to escape the white-out area.

An NTSB meteorologist determined that winds near the accident site at 6,000 ft. would have been out of the north at around 20 kt. This would have resulted in downslope wind flow south of the mountain ridges in the vicinity of the accident site, possibly accounting for the direction at which the helicopter fell.

Soloy Helicopters is based at Wasilla Airport and operated 17 helicopters at the time of the accident. The company employed 20 pilots, many of whom were only seasonally employed. Founded in 1979, Soloy provides helicopter support for various industry and government services in Alaska. It specializes in precision long-line work with drill-exploration programs.

The company had a risk assessment form for the heli-ski operation, but filled it out just once, at the beginning of the season. The director of operations explained that most of the risk factors remained the same for every flight, and the pilot could assess the few variables like the weather. A pilot could decline to take a flight if he felt the weather was unacceptable.

An NTSB survey of three other Alaska helicopter operators who conducted heli-ski or remote operations found that two of them required pilots to do a risk assessment every day and one required pilots to do one before each flight.

We offer conclusions and comments in Part 3 of this article.

Identifying Fault In A Fatal Heli-Skiing Crash, Part 1: https://aviationweek.com/business-aviation/safety-ops-regulation/identi…